|

Introduction The purpose of the present article is to look more closely at the model found in Leslie Howard's film and the ways it was adapted by Raoul Wallenberg to the situation in Budapest in 1944. But first, a brief discussion of The Scarlet Pimpernel will provide some useful back-story. Baroness Emmuska Orczy, Hungarian born but residing in England, wrote The Scarlet Pimpernel, both as a play performed in London's West End in 1903 and as a novel published in 1905. The action, set in 1792, concerns a band of daring Englishmen who make forays into France during the Reign of Terror, "snatching away lawful victims destined for Madame la Guillotine." [2] These Englishmen

The leader of this band is Sir Percy Blakeney, a baronet who pretends to be a mindless and effeminate fool, affecting a "perpetual inane laugh," in order to prevent anyone from suspecting that he is the legendary rescuer of French aristocrats. Even Lady Blakeney, his French-born wife, is deceived by his foppish pose and has no idea as to the identity of the Scarlet Pimpernel, so named because he sends those he will rescue as well as their persecutors a slip of paper "signed with a device drawn in red - a little star-shaped flower, which we in England call the Scarlet Pimpernel" (p. 12). Acting on behalf of the Comité de salut public, Citoyen Chauvelin is the Scarlet Pimpernel's arch enemy. Chauvelin blackmails Lady Blakeney into helping him to lay a trap for the mysterious rescuer, by threatening to have her brother Armand arrested. Ultimately of course, Lady Blakeney discovers her husband's secret identity, bitterly regrets having unwittingly laid a trap for him, Sir Percy cunningly outwits Chauvelin once again and along with his now adoring wife, makes a getaway from revolutionary France and a safe return to England.

Leslie Howard and Merle Oberon as Sir Percy and Lady Blakeney. However Baroness Orczy did not consider Leslie Howard ideal for the part because "he was short and could not look strong enough to dominate certain situations, nor could he tower over Chauvelin, played, as it happened, by a very tall man [Raymond Massey]" (p. 166). And although she disapproved of the film's ending, she stated that all things considered: "I think I may safely say that my pleasure in the presentation of my romance on the cinema outweighed any disappointment I may have felt" (ibid.). The film, directed by Harold Young, picked up no awards of distinction, but did win high praise from contemporary critics. [4] Pimpernel Smith Synopsis In the Spring of 1939, a mysterious rescuer, referred to in the press as the Shadow, manages to save a number of scientists and artists from the clutches of the Nazis, getting them safely out of Germany. His calling card, given to prisoners he is about to liberate, is a note with the words "The mind of man is bounded only by the universe." The arch villain of the film, General von Graum (played by Francis L. Sullivan and clearly modeled on the equally corpulent Hermann Goering) is obsessed with capturing the mysterious Shadow, and is also preoccupied with debunking the idea that humor is a secret weapon of the British. In the summer of 1939, the bespectacled and absent-minded Professor Horatio Smith (Leslie Howard) conducts archeological excavations in Germany. The six Cambridge students he has brought along on the dig are unaware that he is in fact the Shadow. He slips away from time to time on his secret rescue operations, in one striking scene disguised as a scarecrow. Smith's students eventually discover that the Shadow is none other than their "prof," and from then on, assist him in his secret operations. Meanwhile, Ludmilla Koslowski, daughter of a Polish newspaper editor, has been blackmailed into working for von Graum who is holding her father prisoner. Her assignment: to help capture the Shadow, whom von Graum knows will be attending a specific banquet at the British Embassy in Berlin. At this banquet, von Graum and Smith meet for the first time and Smith replies with wit and persistence to the general's absurd claims, e.g. that Shakespeare was a German. It is also here that Ludmilla first sees Smith and immediately suspects that he is the Shadow, informing von Graum of her guess, which is dismissed by the general as ridiculous. She visits Smith's room that night, asking him to rescue her father, but he denies being the Shadow. The next day, having verified that she is in fact Sidimir Koslowski's daughter, Smith agrees to help free her father, whom he tells her is being held at the concentration camp in Grossberg. When Ludmilla tells von Graum that she was mistaken about Smith's being the Shadow, she inadvertently reveals that he must in fact be the mysterious rescuer, since she now knows where her father is being held. Von Graum expects a rescue attempt, but not on the day it is deftly carried out by Smith, in the guise of a revolting Nazi propagandist calling himself Vodenschatz, who intimidates and rudely bosses people around at the Ministry of Propaganda. Through this elaborate bluff, Smith manages to free Koslowski as well as several other prisoners at Grossberg. Von Graum is unable to confirm that Smith and Vodenschatz are one and lets Smith and Ludmilla go, though under surveillance. Smith promises Ludmilla that he will not leave Germany without her. He then arranges for her father and the other prisoners he has freed to escape from Germany to France by train. When the Nazis interrogate Ludmilla, claiming that Smith has left Germany for good and that her father has been recaptured, she admits that Smith is the rescuer. Smith now returns for her, she is distraught but forgiven for having revealed his identity, and the two of them set out on their own getaway by train. At the border station, von Graum's men arrest Smith, and Ludmilla is sent back on the train to France. It is now that Smith is led into a waiting room at the station where von Graum takes charge of his prize prisoner. What follows is a memorable monologue in which Smith replies to the general's claim that Germany will soon rule the world:

"You will never rule the world because you are doomed. All of you who have demoralized and corrupted a nation are doomed. Tonight you will take the first step along a dark road from which there is no turning back. You will have to go on and on, from one madness to another. Leaving behind you a wilderness of misery and hatred. And still you will have to go on because you will find no horizon and see no dawn 'til at last you are lost and destroyed. You are doomed, Captain of Murderers. And one day, sooner or later, you will remember my words."

The general then has Smith placed at the flimsy wooden gate marking the frontier, where he can be "shot while trying to escape." But once again, Smith slips through the general's fingers, disappearing behind the barrier when the general turns away for a moment. Von Graum fires his pistol in the direction of the puff of smoke Smith has left behind from his cigarette, and when von Graum shouts "Come back," Smith - no longer visible and safely on the other side of the wooden gate - calmly replies: "Don't worry, I'll be back. We'll all be back." The Vodenschatz episode However, in the Vodenschatz episode we are clearly shown and in rich detail at least some of the ways in which Professor Smith gets the better of the Nazis. In order to carry out a plan he has devised for liberating Sidimir Koslowski and several other prisoners being held at the Grossberg camp, Smith needs six official permits for visiting the camp and a high ranking officer to accompany him when he enters Grossberg in the guise of Herr Vodenschatz, along with his six students posing as American journalists. He will have to get the permits and the officer he needs at the Ministry of Propaganda, and his visit there is prepared by one of the his students who taps into the ministry's private telephone line and says:

Professor Smith, unrecognizable thanks to a fake mustache and wads of cotton stuffed in his cheeks, and wearing a bowler hat and matching suit, then strides busily into the Ministry, puffing on a cigar. At several points, when he needs to cross a threshold of some kind within the Ministry, he brushes off the guard who tries to question or stop him: SMITH (walking briskly past the entrance guard): Heil Hitler. GUARD: Who do you wish to see? SMITH (without stopping): I've seen. Or again at an inner gate, he turns the situation around, putting the guard on the defensive and defining his role as someone who is there to assist him: SMITH: Heil Hitler. GUARD: No visitors, except by appointment. SMITH (curtly): How long have you been here? You don't know me? Ever heard of the American Department? GUARD: Ah, yes sir. I thought… SMITH (interrupting him): Don't apologize. See if you can find my umbrella. I left it behind the other day. Vodenschatz is the name. After more encounters of this nature, but in which he begins pressing for the permits he needs, Smith finally barges into the office of Steinhof, the department head, along with a subordinate named Graubitz. As this somewhat longer quote will illustrate, Smith captures and holds the initiative at every turn, confusing, and bullying his adversary, and meeting any hesitation to comply with his demands by threatening to complain to a feared superior, in this case Josef Goebbels: SMITH: Now look here Steinhof, where are the permits for the six American journalists. STEINHOF: Permits? SMITH: Yeah, don't you say Heil Hitler any more? STEINHOF (rising from his chair): Heil Hitler. SMITH: Heil Hitler. STEINHOF: I don't think I know you. SMITH: Then what do you know? Have you ever heard of America? STEINHOF: Yes. SMITH: Good. Then where are the permits? STEINHOF: But I... I… SMITH: Now listen. I'm Vodenschatz. The man who got the Nazi Party those nice headlines in America where they don't like you. I'm the man who put the Nazi American Bund on the map. And you never even heard of me. Let this be a lesson to you, Gentlemen. STEINHOF: But ah… SMITH: No, no, no, no. Let me speak. I've come all the way from New York to correct your blunders with the American correspondents. I've spent two whole weeks with them, trying to nurse them into a better humor. This afternoon I was taking them to the Grossberg camp so they could cable the United States and tell them not to believe those stories they hear about the German concentration camps. And you've got to spoil everything. I ask for permits and you haven't got any permits. STEINHOF (to Graubitz): No one told me anything about this. GRAUBITZ: The Gestapo did telephone. STEINHOF: Oh. SMITH: So now you're deliberately obstructing the Gestapo. GRAUBITZ: That would be the last thing I'd do. Perhaps if you'd come back tomorrow… SMITH (to Graubitz): Tomorrow? Do you want me to keep the representatives of six of the biggest newspapers in America waiting outside this building until tomorrow? Unless I get those permits in two minutes, you'll be responsible. GRAUBITZ: I'll be responsible? SMITH: Right! I know what I'll do! (Pointing to the phone. ) Get me Dr. Goebbels. STEINHOF: No, no, Herr Vodenschit.. uh, Vodenschatz. I… I… I'll find the permits. SMITH: Find them, find them. GRAUBITZ (to Steinhof): There are some here, Sir. SMITH: That's better. Now you can fill them out as we go. STEINHOF: As we go? SMITH: Certainly. Didn't I say you are coming with us. STEINHOF: No, no. I have... SMITH: Oh, this is too much. Please. Get me Dr. Goebbels (picking up the phone). STEINHOF (rising from his seat): No, no. I can finish the work at home. SMITH: Ya, that's right. And we've been waiting long enough. Come along. Come along. Smith leads Graubitz and Steinhof from the inner office. SMITH: You know, the trouble with you propaganda boys… You've got so used to telling lies… you don't recognize the truth when you hear it. STEINHOF: Orders are orders. SMITH (to someone walking in the other direction): Heil Hitler…. You know, Graubitz, you're a smart boy. GRAUBITZ: Thank you, Sir. SMITH: Yes, you can do something for me. Ring up the Grossberg camp and tell them we're on the way. Have them prepare everything in the usual Ministry of Propaganda style. And remember: America is a soft-hearted democracy. Get me? GRAUBITZ: Leave it to me, Herr Vodenschatz. GUARD (seen earlier in the scene and now holding out two umbrellas): Your umbrella, Sir. SMITH: Oh, umbrella. (Taking one). Thank you. Smith leading Steinhof toward the exit, stops for a moment pointing at a guard's boots with his umbrella. SMITH (to guard): Dirty boots. Exit. Shortly after arriving at Grossberg with Steinhof and with his six students posing as journalists, Smith has Steinhof knocked out, and his uniform donned by Koslowski while the other prisoners to be freed put on the clothing of the "journalists," who later pretend to have been beaten unconscious. Smith makes an easy getaway in two cars with the prisoners he has rescued, remarking as he removes the fake mustache: "Well, goodbye Vodenschatz. You were the quintessence of all the objectionable men I ever met but you served a noble purpose." Raoul Wallenberg

Raoul Wallenberg in 1944 increasingly frustrated over not being able to do anything about the unbearable scenes he was witnessing. One of his friends stated: "he seemed a little depressed at that time. I had the feeling he wanted to do something more worthwhile with his life." [8] It was at this time that seeing Pimpernel Smith apparently gave a new direction to Wallenberg's plans for the future, as John Bierman reported in these terms:

Two years later, having been accepted by representatives of President Roosevelt's War Refugee Board to carry out a rescue mission in Budapest where he would serve officially as First Secretary of the Swedish legation, Wallenberg carried out in reality the kinds of daring exploits his role-model had performed in Pimpernel Smith. On July 9, 1944, the day of his arrival in Budapest, Wallenberg asked Per Anger, Second Secretary at the Swedish legation, what documents he had issued to the Jews. Anger showed him the array of materials that had been used until then, with varying degrees of success:

These homemade but visually striking "passports" with their official emblems, seals and signatures, stated that "the bearer awaited emigration to Sweden and, until his departure, enjoyed the protection of that government." [10]

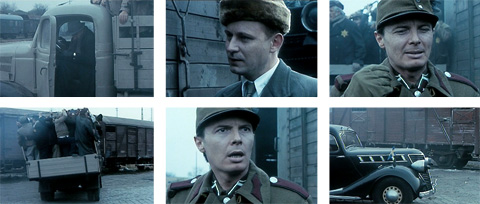

The protective passports were just one of many plans Wallenberg put into practice as part of his rescue mission, which included the creation of "safe houses;" the hiring of hundreds of Jews as embassy staff; providing food, medicine and clothing, even during death marches to the Austrian border; and threatening to have the supreme commander of German forces in Hungary, General Gerhard Schmidthuber hanged when the advancing Red Army arrived in Budapest, unless he prevented the slaughter that had been planned by the Arrow Cross (Hungarian Nazis) of the approximately 70,000 Jews then clinging to life in the ghetto. Returning now to the protective passports, we can consider one of the most dramatic ways in which they were used: namely as a pretext for extracting Jews from freight cars bound for Auschwitz. While written accounts could be cited to illustrate these remarkable events, the account that does the greatest justice to them is an unforgettable scene in the award-winning Swedish film, Good Evening, Mr. Wallenberg, written and directed by Kjell Grede and released in 1990. As the scene opens, a truck is seen driving alongside railroad tracks on which a single freight car is being pushed toward a station by a locomotive. Seated in the cab of the truck are Wallenberg (Stellan Skarsgård) and his driver, Szamosi (Károli Eperjes). All dialogue in the scene is in German, provided here in English translation based mainly on the film's subtitles. Stills are reproduced with the kind permission of Kjell Grede and Sandrew Metronome.

SZAMOSI: Everyone in the Spanish Embassy has gone home. I'm the only one left. But I'm not even employed there. We have embassy stamps, flags, and official cars at our disposal. So the Spanish Embassy… is me. WALLENBERG (smiling): Not bad for a Jew with false papers. SZAMOSI: Lies and deception lead to success. With real papers, you die. (He looks over at the Arrow Cross guards holding on to ladders at the back of the freight car. ) Here they are supposed to be transferred. If they leave with the next train they'll never come back. (As the train comes to a halt, Szamosi parks the truck in a position perpendicular to the tracks.) How many have Swedish passports? WALLENBERG: Five. SZAMOSI: Five. Out of fifty-two. WALLENBERG (putting on white gloves): We have to do it in less than two minutes. Otherwise it's no use. SZAMOSI: Put on the fur cap. Without it you're lost. Wallenberg fits a fur cap onto his head. They both look through the rear window of the cab, as Arrow Cross guards pull open the sliding doors of the freight car.

SZAMOSI: Now? WALLENBERG: Now! Szamosi backs the truck, so that the loading platform is flush against the opening of the freight car, then hurries out of the cab and climbs up onto the platform. Wallenberg, who has also descended from the cab, hands him a paper. Arrow Cross soldiers approach, led by a sergeant.

WALLENBERG (in a loud angry voice, addressing the sergeant): This is a very serious mistake for a minor official. Meanwhile Szamosi is now inside the freight car, coaching the men who all have yellow stars sewn onto their coats. WALLENBERG (begins calling out names on a list): Schönberger. In the freight car, Szamosi instructs a man to say "Ja, Ja" and pushes him out toward the platform. The sergeant puts his hand on Wallenberg's arm WALLENBERG (to the sergeant): Be quiet. (Then resuming the roll-call.) Weiss. SZAMOSI (off-screen): Ja! Wallenberg circles around, waving the sergeant over and beckoning him with his gloved hand, so that the sergeant, in following Wallenberg's instructions and changing his position, now has his back to the truck. WALLENBERG (in a reproachful, lecturing tone): Herr Sergeant. A labor battalion that is supposed to carry out repairs at the Swedish and Spanish Embassies. Repairs that cannot be delayed. (Waving a handful of protective passports.) They have Swedish passports. Understood? (The sergeant, who can't get a word in edgewise, looks exasperated. Wallenberg resumes the roll-call.) Fischer!

SZAMOSI: Ja! (He grabs a man, has him raise his hand, and pushes him out toward the platform. ) WALLENBERG (now yelling at the sergeant): The repairs can't be delayed. Do you understand what that means? Herr Sergeant! (Resuming roll-call.) Fingelmann! SZAMOSI: Ullman? (He looks around.) Ja, Ullmann. WALLENBERG (handing his pack of protective passports to the sergeant): Here, check for yourself. (He turns toward the rest of the squad, then back to the sergeant. ) I want the names of all of your men. (The sergeant is now facing the truck once again and looking at the protective passports. Wallenberg walks over to him, snatching the papers from his hand. ) What is it with you? Answer me! Don't you speak German? (He gets the sergeant to look away from the truck. ) SERGEANT: There should be… should be a… WALLENBERG (off-screen): Are we supposed to do the repairs ourselves? Szamosi hurries into the driver's seat in the cab of the truck. WALLENBERG (keeping an eye on the truck, which the sergeant cannot see): How do you imagine that? You're going to pay for your lies. The sergeant begins to reply but has trouble formulating a single word in German, then turns to see the truck pull away, with all 52 Jews on the loading platform.

WALLENBERG (off-camera, and still haranguing the sergeant): That was a very unusual transfer. Very unusual and you're gonna pay for it. (Now Wallenberg sees his embassy car pull up, with a small Swedish flag mounted on the fender.) You're totally unreliable. You don't say a single true word. (Getting into the car.) One asks oneself if you know what honesty means. (As the car pulls away, Wallenberg removes his fur cap. Now viewed from inside the car, Wallenberg, looking weary, quietly addresses the unseen driver while removing his gloves.) You were late. 30 seconds.

In this scene, a kind of composite based on a variety of accounts in the literature describing Wallenberg's activities in Budapest, [11] it isn't difficult to see how Wallenberg might have taken what he needed from Leslie Howard's Professor Smith and adapted it to the present circumstances - above all, the use of bullying and insults, of a constant stream of threats and blame, keeping the adversary on the defensive at every turn and never letting him capture the initiative, the verbal and gestural flourish, the hammering away with an elaborate pretext, the perfect or near perfect timing of efforts coordinated with confederates, etc. There are also of course important differences, since here for example no disguise was needed, there was no secret identity to hide. But the spirit and manner of the two performances unmistakably share the same essential qualities. Leslie Howard's death One is that German spies mistook another passenger, Alfred Chenhalls - Leslie Howard's cigar-smoking, heavy-set, balding accountant - for the British Prime Minister. Churchill himself believed this to be the case, and when describing his return to England from Gibraltar at about the same time, he wrote:

Another explanation is that the Luftwaffe pilots were unaware that the plane they shot down was a civilian aircraft. This at least was claimed by one of the pilots who had taken part in the operation - Oberleutnant Herbert Hintze - who stated that it was only after they had opened fire that the air crews discovered that the enemy aircraft they had attacked was a civilian plane. [13] And a third explanation is that the Nazis had specifically targeted the flight because they knew that Leslie Howard was on board. Though Ronald Howard believed that the mystery of the attack would never be solved, he also suggested that the presence of his father on the plane, as well as that of T. M. Shervington (Chief of Shell Oil), "may well have been the main motive, the basis for the [Luftwaffe's] search and final interception of Ibis" (op. cit., p. 230). Ronald Howard further evoked another argument in possible support of this explanation, namely:

Furthermore, in discussing reactions to his father's death, including those published in Germany, Ronald Howard wrote:

In this context as well as in the relationship between Pimpernel Smith and Raoul Wallenberg, the boundaries between life and art, reality and fiction, are not nearly as clear-cut as they are generally thought to be. Finally, Raoul Wallenberg also met a tragic fate soon after fulfilling his mission in Hungary, and the mystery as to why he was arrested by the Russians in January 1945 and the fate he met while in their custody, now appears to be as insoluble as the mystery surrounding the Germans' attack on the Ibis. These tragic endings for two lives, focusing each in its own way on the outwitting of Nazi executioners, constitute yet another parallel between Leslie Howard and Raoul Wallenberg. Epilogue In a telephone conversation on September 22nd, 2009, Nina Lagergren said that to her knowledge, Raoul Wallenberg did not think at all in terms of carrying out rescue operations in Budapest until the Spring of 1944, when he was chosen to organize a rescue mission for Hungarian Jews by Iver Olsen, who had been sent by Roosevelt to Stockholm as an official representative of the War Refugee Board. According to Nina Lagergren, it was therefore not the case that seeing Pimpernel Smith gave Wallenberg the idea in 1942 of taking on the Pimpernel role in Budapest in 1944. Nor did he subsequently mention Pimpernel Smith to his sister. So much for what now appears to be too simplistic a view of the effect of the film on Wallenberg when he first saw it. However, if the film was not the catalyst that first set Wallenberg's plans in motion, it can still have defined the dramaturgy that he would ultimately put into play. On the basis of Wallenberg's statement to his sister in 1942 and the striking similarities pointed out above between Leslie Howard's performance, particularly in the Vodenschatz episode, and Wallenberg's modus operandi in Budapest, there is every reason to believe that once committed to his mission at the Swedish legation in Hungary, Wallenberg found in Pimpernel Smith a role-model he could adapt to the situation at hand when facing down Nazi and Arrow Cross guards and snatching prisoners from their grasp. It is in this respect that the remarkable rescue of countless lives in Budapest involved at least in part the transmission of a heroic model from Leslie Howard to Raoul Wallenberg.

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||