The film adaptation of Stieg Larsson's popular crime novel, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, introduces Mikael Blomkvist, the male protagonist, in one of the opening scenes standing on the front steps of a court building, surrounded by journalists and microphones and being interviewed by a female journalist who asks him what it's like to be a loser. Blomkvist looks pale and rather introverted, and although he is standing several steps above the crowd of journalists, he appears small and defenceless. In the scene that follows we see him at a Christmas celebration with the editorial board of the journal Millennium, where he is an editor and journalist. A beautiful woman tries to persuade him to fight back even though he has lost the trial - but he announces his decision to resign from his job, saying that he was naïve to have believed in a story that proved to be false. Several scenes later he leaves the celebration and retreats to the home of his sister and her family, where we find him clad in an apron, baking cookies in the kitchen. At this point the phone rings and he is persuaded to accept a case. Thus the male protagonist enters the plot in a traditional female role: defeated, victimized and finally wearing an apron in a kitchen. By contrast the female protagonist, Lisbeth Salander, enters the film taking photos of Mikael Blomkvist as he leaves the editorial office. Observing him from her hiding place, she is dressed in black leather with heavy eye make-up, with black lipstick and pierced nose and lips. In the first sequence we see her in fragments and in profile, concentrated on her camera and later on the computer, where she hacks her way into Mikael Blomkvist's files. To make a long story short: He is shown as a pale, soft, feminine figure; she is shown as an androgynous heavy punker, in control and as aggressive as a hardboiled masculine character. In this article we wish to focus on the gendered bodies of the two main characters, their physical appearance and their bodies as physical artefacts in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo [1]. While the plot line is much the same in the novel and the film, the characters differ. Whereas the gender of the characters in the novel is ambiguous, the film shows us simply gendered characters, albeit in reverse. The male character is soft and passive, while the female protagonist is hard and has a body inscribed with demonic symbols. Our main argument is that the adaptation from novel to film involves an alteration of the gender representations in the two main characters, and that this alteration corresponds to the genre-specific and media-specific conditions associated respectively with the genre thriller versus crime fiction and with the format of the film versus that of the novel. In examining these differences in relation to The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, we draw on the fact that gender is a central issue in Nordic crime fiction as bestseller and cultural commodity. Stieg Larsson as feminist author? Crime fiction has traditionally been seen as a male dominated genre (Agger 2009) but since the 1990s we have witnessed a boom in crime fiction created by women and with female protagonists. American authors such as Sarah Paretsky and Marcia Muller were already publishing feminist crime novels in the 1970s and the 1980s, but since 1990 Scandinavian and especially Swedish writers have achieved great popularity in Europe (Klitgaard Povlsen 1995). Liza Marklund, Åsa Larsson and Helene Tursten are the bestselling authors of novels that have often been adapted for film and television. They can be said to have created feminist fiction by presenting female protagonists that are competent, strong and clever and who act effectively in a society often dominated by men. But male authors such as Henning Mankell have also contributed to this new type of fiction by writing about soft, melancholic male police officers engaged in crimes that involve strong female offenders who react with vigilante violence to male rape, murder and so on in their pasts (Klitgaard Povlsen 2006). In a debate in Sweden and Denmark in 2007 that looked at male and female crime writers and directors, Stieg Larsson was presented as a feminist author who wrote better than his female counterparts (Hjarvard 2007). It is in this context that we see the adaptation from novel to film and the tie-in effect between print and film/television (Feather and Woodbridge 2007: 218, Geraghty 2009: 91) that often creates a bestseller in both media formats. Both in print and on screen, Nordic and especially Swedish crime fiction has often focussed on equal opportunities, offering a critique of traditional gender roles and presenting ambiguous strong female characters and soft male characters.

Ambiguous characters and relationships are one of the key features of Nordic crime fiction (Agger 2009). This ambiguity can be seen, for example, in the way that characters struggle to combine the roles of responsible parent and professional policeman, caring partner and efficient investigator, or even try simultaneously to stay on the right side and the wrong side of the law, as in the case of Henning Mankell's police detective Kurt Wallander. This ambiguity can also be seen in the way that specific places and communities are presented both as familiar, picturesque locations that evoke nostalgia and as scary crime scenes (Waade 2007). The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo presents all these kinds of ambiguity, including an ambiguity with regard to gender, in which the characters reflect different aspects of masculinity and femininity. Mikael and Lisbeth in relation to Astrid Lindgren's work

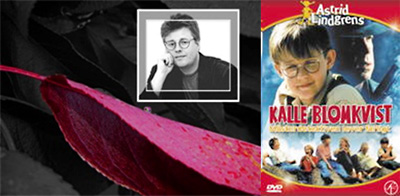

Unlike Mikael Blomkvist, the female protagonist Lisbeth Salander is not initially presented from the inside but rather through the eyes of her boss, Dragan Armanskij. He sees her as an extremely clever security detective, who is "pale and anorexic with very short hair and pierced nose and eyebrows. She had a two-centimetre tattoo on her neck and […] a tattooed dragon on her shoulder blade. Her natural hair colour was red, but she had dyed it ivory black" (p. 38). In short, Salander is seen as clever and hardboiled, and on page 53 of the Danish edition, she is referred to for the first time as a kind of Pippi Longstocking, Astrid Lindgren's most famous character. Like Pippi, Lisbeth is an unorthodox individualist, living on her own and taking the law into her own hands, and like Pippi she ends up with a lot of money. While Kalle and Pippi are examples of the girl-boy and the boy-girl that we often see in 20th century children's literature, Stieg Larsson's novel transfers these utopian figures to a grown-up universe. By contrast, the film re-traditionalizes gender roles and especially sexual relationships. In the novel, Lisbeth Salander has sexual relationships with women until she meets Mikael Blomkvist, as he has sexual relations to several women. In their relationship, the two protagonists in the novel both adapt somewhat to prevailing gender roles, and both are less involved with other women. The film: from reversed gender stereotypes to a true love story In the adaptation from novel to film, the producers have made certain dramaturgical choices that emphasise these gender stereotypes. In the love-making scene, for example, it is Lisbeth who plays the typically masculine part; it is she who takes the initiative by entering his room at night, and she who takes the active and dominant position, sitting astride him while they make love showing her naked, well-muscled and hard body. Mikael assumes a passive role, allowing himself to be controlled and seduced as he lies flat on the bed. When they are finished, Lisbeth leaves the room and wants to go to her own bed to sleep. Mikael is left in his bed and asks gently: are you leaving? She looks at him and leaves. In this scene she is presented as a masculine lover who takes control and initiative and whose physical and sexual needs take precedence over feelings and emotional relations. Later, in the investigation of the murdered women, it is also Lisbeth who figures things out, takes initiatives and makes plans and decisions, while Mikael can hardy drive the car they are renting and is frightened and unsure of what to do. Lisbeth is the technician and computer expert, and it is she who installs surveillance in the cottage where they are living: a decisive move in enabling her to solve the crime and ultimately save Mikael's life. And it is (of course) Lisbeth who succeeds in discovering and punishing the serial killer Martin Vanger. Lisbeth is the real hero of the story. At the same time, however, another story is unfolding, and another form of gender representation and gender relationship is emerging. This other story concerns the love relationship between Lisbeth and Mikael. In this story Lisbeth is in the process of becoming a woman and Mikael a man. Again, it is Lisbeth who first takes the active role in restoring Mikael as a lover and an attractive man. It is also she who makes it possible for him to take revenge on the true villain of the story, the financier Wennerström. She is the anonymous giver in the story. It is thanks to her investigation and actions that Mikael in the end achieves redress for his loss in court at the beginning of the film. Another interesting dramaturgical choice with regard to the main characters in the film concerns the way in which their various other sexual relationships and affairs are eliminated. Thus Mikael's long-term relationship with his married female boss and his love affairs while he is working for the Vanger concern evaporate, as does Lisbeth's lesbian relationship and friendship with another girl. In the film, these relationships are barely even suggested. This is also why the love relationship between the two protagonists and their growing feelings for one another stand out so clearly and unambiguously in the film as a traditional love story that presents typical gender relations. While Lisbeth is reinstating Mikael as a lover and a winner, Mikael is reinstating Lisbeth as a sensitive feminine woman. Thus as the film progresses, Lisbeth gradually becomes more soft and careful; her black makeup, black lipstick and tough armour slowly disappear, her beautiful body and profile are revealed and her feelings and charm emerge. Mikael, as a person, makes it possible for her to open up and develop as a person too, and she is shown as a much more soft and feminine character at the end of the film than she was at the beginning.

She falls in love with him without really having the capacity and courage to acknowledge this and, for example, tell her mother about her feelings for Mikael. In the scene with her mother, however, another feminine characteristic emerges; Lisbeth becomes a daughter, showing concern for and feeling sorry for her mother. In the course of the story she develops from being a wounded, bitter and lonely child to becoming a mature, empathetic and forgiving woman. Because of Mikael's calm and emotionally open attitude towards her and Lisbeth's growing feelings for him, Lisbeth is transformed from a tough, black, distanced, heavily made-up person who smokes continuously into a naked, vulnerable, fragile person and an attractive woman with no makeup. It is Lisbeth's development as a person and the developing love story between Mikael and Lisbeth, that are emphasised in the movie. Media formats and genre perspectives In the adaptation from novel to film, certain obvious media-specific conditions come into play, e.g. the duration of the plotted story (Stam 2005). In a novel, the author has many hours at his disposal, and in Stieg Larsson's case over six hundred pages and hundreds of reading hours are used to tell the story. This amount of time makes it possible to give an expanded and complex characterisation of the protagonists, and the reader has even more time to get into their minds, their relationships, their experiences and actions, in so far as the reading time is usually longer that the duration of the plot (some crime fiction enthusiasts of course read the whole novel at one go). By contrast, the film director has only about 120 minutes to tell the same story, s/he has to make cuts and priorities so that the story fits into the film format. The dramaturgy and the presentations of the characters have to be effective and simple so the plot and conflict emerge clearly especially in films directed at a global mass audience the contrasts are often exaggerated and traditionalised (Leitch 2008: 68). Nevertheless, many audiences already know the novel and may glimpse it behind the film (Geraghty 2007: 195). To secure international distribution and popularity and maximize ticket sales, the combination of crime and love story is particularly favourable, as we know from several other crime series and action movies. Following recent adaptation theory we find this interesting but we do not see it as a proof of quality. It does however tell us something about how a global bestseller-film can tell a story that for most viewers is already known in another printed version (Hutcheon 2006) that becomes part of the film experience. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||