| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In this article I am going to discuss a small selection of humorous scenes from different kinds of films, ranging from silent comedies by Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton to the fantastic world of Tim Burton. Focusing on the visual humour of cinema, the question is how specific elements in the examples work, and which mechanisms can be said to enable viewers to have fun when watching scenes or sequences. In other words, what qualities and potentials of cinema are used to articulate and cause effects that the audience can experience as amusing and funny? Playing with camera sight and viewer's view

The surprise and the amusing effect are not just caused by what is going on or that the man is seasick or fishing. Arnheim points out that the key is not the character and his actions, but the fact that the camera is positioned at a special angle in relation to him. "The element of surprise exists only when the scene is watched from one particular position" (Arnheim, 1957, p. 36-37). If the scene had been shot from another angle, for instance directly from the seaside, the idea of Charlie being seasick would not have surfaced at all. Instead the viewers would immediately realize that he was fishing. As Arnheim concludes, Chaplin's staging is not merely aimed at the subject matter, or the event in itself, it is focused on the actual cinematic practice because the effect is realized through the use of a specific film technique (ibid, p. 37).[1] In the work of another artist of film comedy we can find further examples that may help illustrate how cinematic staging can articulate the meeting between film and audience in literally funny ways. In Sherlock Jr. (1924) Keaton plays a young man who is a "moving picture operator" in a movie theatre, but who also dreams of becoming a great detective. One day, while projecting a film, he falls asleep and dreams himself, his girlfriend, her family and his rival into the film. Keaton shows us how the hero's better self enters the screen and, as a real Sherlock, is able to solve the mystery and in the end win his sweetheart. In one of the dream scenes the very elegant young Sherlock is checking his attire in front of a large mirror (fig. 3). Wearing a white tie and top hat he buttons his gloves, his assistant hands him his walking stick, and - he leaves the room through the mirror (fig. 4)! To underline the visual joke the assistant ends up standing in the opening with one leg in each room (fig. 5).

Actually, there was no mirror at all; just an opening onto the next room, and what we saw as a reflection of the room and the things behind our hero are exact replica props instead. The key to this visual joke is the staging: in this case the combination of set design and camera position. The result of this is a framing of the shot that leaves a clear view of the wall and "mirror" on the left side of the screen, which makes it possible for Keaton to play the magic trick on the viewers. The ingredients he uses are a combination of camera angle, visibility, and framing. Besides presenting a most enjoyable comedy, Keaton's film is an experiment with and a cinematic essay on the potentials of the film medium.

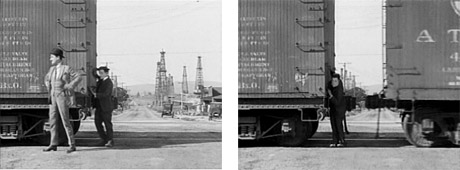

Moreover, when a cut takes us to the room Sherlock Jr. enters, he goes to a large safe, turns the combination lock, opens its door, and leaves the house, crossing a street between cars and trams (fig. 6-7). Once again, the viewer is led to believe and expect things, which turn out to be quite different from the first impressions. Of course, the fact that we are watching a dream means that anything is possible, and in retrospect it makes Keaton's "cine-magic" experiments plausible.[2] But, that said, the surprise and the humour are not less effective. The amusing transformations take place in front of our eyes, and they are the result of Keaton's inventive explorations of the medium of the moving pictures. The effect results from what we can see as viewers, plus what is disclosed or added next. That is, an interplay between a presentation on a carefully defined basis and what this allows to be visible, and the new and surprising element, which has been present all the time, but only shown or made clear the second time around. The amusing surprise results not just from the event or what the characters do or don't do, but from the way the event is sculpted cinematically. Both Arnheim and Münsterberg have made the pivotal argument that the way film pictures are constructed, as well as the way we comprehend them, rely on the fact that the moving images must not be mistaken for reality. Arnheim concludes that in general the potential of cinema to put plausible illusions on the screen is due to "the unreality of the film picture altogether" (Arnheim, 1957, p.14). When Münsterberg investigates the aesthetics of film, he too underlines that the recorded material, which has to be shaped artistically before it is projected on the screen, in the process is separated from reality: "The screen too suggests from the start the complete unreality of the events" (Münsterberg, 1916, p. 75). Film is an artificial material, complete with manipulative techniques and distortions on the two-dimensional screen, and our perception and understanding of it depend on how each film articulates its raw material. As seen in the examples above, this may be part of the reason why it is funny when a film suddenly makes it clear to the viewers that it is teasing them. The Fun of Dimensions Apart from this playing with staging in depth, I will add another visual gag that Keaton makes use of in both The General and Sherlock Jr. While shadowing his rival in the latter he tries at one point to hide behind the corner of a box car on a railroad track (fig. 8-10).

In The General, Johnny Gray (played by Keaton), who is fighting for the South during the American Civil War, at some point tries to free his sweetheart from the troops from the North. At night the house where she is kept prisoner is shown from the outside, a soldier keeping guard. As in the above-mentioned example, it is hard for the audience to detect any real depth in the frame. More so because it is dark and the rain is pouring down. Because of this flatness in the picture it comes as a surprise, when suddenly the guard is hit on the head with a long wooden stick from a chink of the door. Johnny has taken the stick in the house and barely noticeably opened the door a little in order to knock out the soldier. The viewer's amusement is not caused merely by the fact that Johnny neutralizes the enemy, but by the recognition that the surprise comes out of nowhere and, especially, that it is the result of Keaton's "flatness trick." Consequently, we can conclude that the laughs we get from both Chaplin's and Keaton's ways of using the motion pictures draw upon the fact that we as viewers respond to the way the cinematic presentation plays with our attention. In this kind of visual humour a meta-level of communication is at work when narrator and audience meet. Burton's Chocolate Factory My last example to illustrate the potential of visual humour in the medium of cinema and its range of possible manipulations of the motion pictures is taken from Tim Burton's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005). In this article I have focused on visual humour and in a number of cases found that the effect occurs when the viewers can recognize how the director reaches out to them. This is due to the fact that part of the fun is precisely the experience or discovery of the stylistic features the director makes use of in his "tricks" in order to make the viewer laugh. Consequently a mutual understanding between director and viewer has developed on a kind of meta-level. It may sound terribly technical, and perhaps even boring, to talk about meta-consciousness in humour and good laughs, but I think that my examples have shown that it is in fact part of the fun. In Burton's film the owner of the chocolate factory, Willy Wonka, has launched a campaign in order to win back market shares. Children who find a Golden Ticket when they buy one of his Wonka Bars are invited to come and spend a whole day in his mysterious factory. Five children get the chance, and he shows them his secrets and inventions. When they enter the Television Room (fig. 11-16), Willy Wonka says that it is his testing room for his "very latest and greatest invention: Television chocolate". The question is that if television can "break up a photograph into tiny little pieces", send them through the air, and reassemble it at the other end, why can't he send a real chocolate bar through the television all ready to be eaten? Of course the others tell him that it is impossible. But while they talk, they pass a television set showing the scene with the anthropoid apes and the giant monolith from Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968; fig. 11); and actually it comes into use a little later. He calls for his workers to bring in a bar of chocolate, which he will send from one end of the room to the other "via television".

Precisely at this moment the music Kubrick used fades up: Richard Strauss' "Also Sprach Zarathustra" fills the room - and Burton edits his pictures to match the music, the same way as Kubrick did four decades ago. The chocolate bar is gigantic, because as Wonka explains, "on TV you can take a regular size man, and he comes out this tall", showing a height like fifteen centimetres with his fingers. The chocolate is placed in a large transparent cube (fig. 12), and to the sound of the Strauss hymn Burton practises a kind of "space camera work" and an editing much like Kubrick's. In the "2001-white" room a white television camera is operated to move almost like a space ship, and suddenly it makes the chocolate bar disappear. Wonka shows them that it materialises in the television set on the opposite side of the room. We see it replace the monolith in front of Kubrick's apes, and the child hero, Charlie, is able to reach into the television and take out the perfect piece of chocolate (fig. 13-18). It has precisely the right size, and it even tastes great. With very simple means, but also very elegantly Burton shows how Charlie reaches into the television cube, and from a tiny version of the "2001 world" takes the bar back into the material world. The fun goes on for a while with a discussion of teleportation and a boy who jumps into the "tele cube" and is transported into the television set, but is also downsized accordingly! Wonka assures his father that they can just lift him out too; but because he is so small, they have to stretch him the same way they can stretch the candy at the factory. Unfortunately this leaves him in a rather bad shape, and very thin. As in the other films discussed above the humour lies in the way Burton draws attention to a series of tricks and their artificiality, as well as in the joking references to Kubrick's science fiction film. First impressions and well-known phenomena are redefined - in fact much the same way as in Keaton and Chaplin. The directors display their trickery through staging and camera work, and they contact their audience by mobilizing meta-levels of understanding. The very unreality of the film picture that Münsterberg and Arnheim emphasize is the basis of the directors' manipulation as well as the prerequisite of the visual humour. Burton's very recent film makes use of the same kind of "visual magic" as the old masters, and the possibilities of computer animation and CGI are used to connect dream worlds and reality the same way as Keaton did in for instance Sherlock Jr. The surprise and the amusement in his film are of the same family as the fish Chaplin produces in The Immigrant. They articulate their visual humour in order for us, their audience, to have fun. They know this strategy; they also know that we know that they know. They blink their eye, and together we laugh. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||