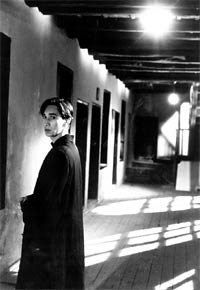

Milcho Manchevski has to date written and directed two feature films: Before the Rain (1994), which won thirty awards at international festivals, including Best Film in Venice, Independent Spirit, an Oscar nomination, and a place in The New York Times' book Best 1,000 Films Ever Made; and Dust (2001), still unreleased. He has also made over fifty short films of various kinds (experimental films, documentaries, music videos, commercials), and has won awards for best experimental film (for "1.72" at the Belgrade Alternative Festival), best MTV and Billboard video (for Arrested Development's "Tennessee," which also made Rolling Stone magazine's list of 100 best videos ever). He is the author of a conceptualist book of fiction, The Ghost Of My Mother, and a book of photographs, Street (accompanying an exhibition), as well as other fiction and essays published in New American Writing, La Repubblica, Corriere della Sera, Sineast, etc. Born in Macedonia, he now lives in New York City where he teaches directing at the Tisch School of the Arts at NYU. I'd like to start by asking about unhappy endings. It may be that my entire approach to this issue is wrong, but what I am most curious about is this: how can it be that a film that ends with the main character dying can leave the viewer feeling satisfied with the ending? I don't know why and how that happens. But I know that it does happen. And probably it has to do with what we get out of a film as we leave the movie theater. Obviously we don't need the conventional "and they lived happily ever after" as the element that's going to leave us satisfied. I've never really thought about it specifically. It's more of an intuitive or an instinctive thing for me. When I do it, it's because it feels like this is the way a film should end. In parenthesis, I could tell you for example that when I wrote the outline for Before the Rain, Kiril - the young monk - was gunned down at the end of the first act. But somehow as I started writing the script, it just didn't feel right… it's as if he wanted to live so much independently of my desire to kill him, that he just refused to die; so I let him live.

I don't know what it is. To me, it's like when you're listening to Mozart's Requiem. It's immensely sad and at the same time it's immensely elating. Perhaps it has to do with the pleasure one gets from a work of art. If things in a work of art make aesthetic sense, if they click, because of how the work was made, how things flow together, how you sense the person - the artist - coming through, stepping down from the paper or from the screen or from the speaker, then the audience gets pleasure out of the art regardless of the conventional understanding of the "feeling" (tragedy, happy ending) the work itself deals with. That's what makes it satisfying, rather than knowing that somebody lives happily ever after. In the end, we all die anyway. Maybe it's about those moments of happiness and creation in between. So again: I don't have a really rational explanation of why, but I know that tragic endings do make sense. Which is not to say that I don't enjoy films with happy endings as well. The real question is: what is a happy ending? A film or a story that takes you for a very satisfying aesthetic (and thus emotional) journey is something that has more of a "happy ending" than a film that neatly resolves everything and leaves the main characters married happily ever after, but is aesthetical cowardly and conservative and not terribly creative. I understand that in your own writing, you deal with this in an intuitive way. But I wonder if there aren't some specific strategies that can help the viewer to accept the sense of loss when the hero dies. For example, at the end of Before the Rain, the very fact that the rain finally falls on Alex somehow frames his death in a kind of metaphor. If I try to analyze the things I've directed - and the fact that I've directed them doesn't necessarily mean that my analyses are right - my guess would be that things that feel essential to a tragic ending are more important than the actual tragic ending itself. Things like self-sacrifice, rebirth, cleansing. So in a way, maybe what's happening in these features is that they're encapsulating the essence of sacrifice and rebirth as part of the same whole. So in that sense, you can say "They lived happily ever after" in a larger perspective. Another thing I noticed is that when Alex is riding on the bus to his village, and talking with a soldier, the soldier says: "What are you doing here? Don't you realize you can get your head cut off?" And Alex says, "It's high time that happened." This is a kind of foreshadowing or even acceptance on his part of what was to come. Well, at that point in his life, he is fairly fatalistic. And I think that as a character, Alex has probably always been fatalistic, but at the same time, very active. Fatalistic but positive. However, at this point in his life, he perceives himself as someone who's done something terribly wrong. So he's become more of a tragic fatalist. Of course, he packs it in with a sense of humor, with a joke, so you are never sure - and I don't think he's ever sure - how much of it is a joke and how much of it is fatalistic acceptance of life's tragic unfolding. Perhaps he's hoping that his fatalism and his acceptance of responsibility will fend off tragedy. In the same scene, we see him play with the facts, as in a sick joke. When the soldier asks him about his girlfriend, Alex says "Oh, she died in a taxi," even though we know she's alive. And we realize: oh, that's when they broke up - in a cab. That is also more like the way people really talk. You know, people don't always deliver what the audience needs them to deliver, in order for the story to advance.

You kill off some of your main characters in Dust as well. Yeah, I am still the same filmmaker with the same take on things as in Rain, except Dust is more complex, and more playful. It switches gears and mocks genres. Yes, there's quite a bloodbath in the film. But mind you, not even close to how many people die in Shakespeare's plays. Not even a fraction. Or in the Bible, for that matter. I found this interesting thought by Bergman, who says that film is perfectly legitimate way for society to ritualize violence. Mind you - ritualize, not glorify.

Is it OK if we move into the area of film and politics, and maybe compare Before the Rain to Dust? In Before the Rain, if I'm not mistaken, you do everything you can to show the conflict from both sides, from both points of view. Actually, to the detriment of the proverbial Macedonian side. If you look at the characters, the more aggressive ones are all Macedonian. As a sign of good will, because Before the Rain is not about sides in a war, it's about right and wrong, and love and understanding. And it's about how humans behave. But go on. Do I remember correctly that there is a point where Alex says "Take sides!" Ann says "Take sides!", "You have to take sides." And he says, "I don't want to be on any of their sides. They're all idiots." Now Dust portrays a very different situation, where you have the Turkish invaders opposed by the Macedonian rebels who are defending themselves, defending their own land. And there, there is clearly a taking of sides. Is this what gave rise to misunderstandings about your politics? All killers in Dust, whether Macedonian, Turkish, Greek, Albanian or American are - killers. Not particularly nice people. They are, of course, nuanced characters, since we are not in a Schwarzenegger or Stallone movie. The really good guys are the ones who give, and in that respect the proverbial good guys are all women - Neda, Angela, Lilith…

The very second question that I was asked at the press conference in Venice when Dust opened the Venice Film Festival, was - and this is pretty much a quote: You've made a racist film, because it portrays the Turkish army and Turks in a bad light. This obviously had to do with an attempt [on my part] to keep Turkey from becoming a member of the European Union. End of quote. (Laughter.) This is on record from a respected English journalist and reviewer. (What's next - I am going to get the US out of Iraq with my next film?? Then I'll liberate Tibet, and then solve the Palestinian issue.) So how do you answer something as ridiculous as this? It's obviously an assassination. Do you dignify the concept of someone feeling free to slander you and to project his prejudices upon yourself, by responding to it? What do you say first? Do you debate the fact that both with my actions in my life and in my films, I have shown that I am not a racist? That I deplore racism of any sort (and let's not forget - neither the Holocaust nor the atom bomb were invented in the Balkans)? Do I talk about the tolerance-building effect of my films, or about the multi-ethnic make-up of the crew who worked on my films (13 nationalities on Before the Rain, more on Dust), or about girlfriends and friends of other ethnicities I've had? It's ridiculous. Actually, it's much more than that - it's insulting, manipulative, ill-intentioned, arrogant and - racist. Do you sue the guy for slander? Do you say: "Hey, it's not even in this film. You're misreading it." Do you say: "Actually, you have a racist past as a member of the Orange militia in Northern Ireland," as that particular critic did? Basically, you're a sitting duck. And then I heard - I didn't even read it - that there was an article published in Croatia, in a magazine that has distinguished itself as an ultra right-wing nationalist publication, taking me to task for not understanding the plight of the Albanians in Macedonia. I'm sure their reporter who's never been to Macedonia understands it much better from Zagreb. (Laughter.) I can't really speculate as to why industry insiders chose to misrepresent Dust. As a matter of fact, a lot of people misrepresented Before the Rain as well… but in a different way. (I have probably repeated literally hundreds of times in interviews that Before the Rain is not a documentary about Macedonia. It's not a documentary about what used to be Yugoslavia. And it's not a documentary at all. I wouldn't dare make a film about the wars of ex-Yugoslavia of the 1990s because it's a much more complex situation than what one film can tell you. It should be a documentary; it shouldn't be a piece of fiction, because a piece of fiction is only one person's truth and a documentary could claim to be more objective even though they seldom are. And finally because I wasn't even there when the war was getting under way. I thought it was obvious from the film, because it is so highly stylized that I don't think anyone who's watching it while awake could see it as a documentary. Just the approach to the form, to the visuals, to the landscapes, to the music, the characters and everything - and finally the structure of the story - show that it's obviously a work of fiction. Still, some people chose to see Before the Rain as a "60 Minutes" TV segment, a documentary on the Yugoslavia wars. But that misrepresentation - even if it could be as damaging - it wasn't as hostile as the misrepresentation or the misreading of Dust. )

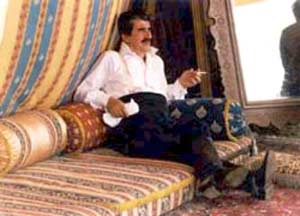

With Dust, there are a couple of things I could start thinking about out aloud, and I haven't done so in public so far. Number one: as a filmmaker, you are often put in a position to debate other peoples' perceptions of you, their projections of you and their projections upon you. As an object of their analysis, you can never properly discuss their motivation, their prejudice or their misreading of the text. Or their real intentions. Yet, although they are active subjects who shape, reflect or bend the launch or the very public life of a film, they themselves and their motivations are conveniently not part of the debate. The second thing that I would like to think about out loud is that a filmmaker's or an artist's political views, a filmmaker's or an artist's life, and the works that he or she creates, are three completely separate things. And I subscribe very much to what Kurt Vonnegut said; which is, if you bring your politics into your art, you are bound to make shit. I think daily politics doesn't belong in art. The artist has other, more interesting and stronger points to make than just who's in the White House these four years and will s/he go to war. Such as how absolute power in the hands of people with corrupted spirit can cause thousands of deaths. As far as Dust is concerned, it's a film about Angela and Edge, an old woman and a thief. And about Luke and Elijah, brothers from the American Wild West. And about Neda, who gives birth while dying. It is about small people caught in the big wheels of history, who are big when they love and when they give. It's about the thirst to tell stories. About the question what we leave behind: children, pictures, stories or dust. About responsibility and self-sacrifice. It's not about ethnic conflict. The conflict we see in the film is not really ethnic; it's like all wars: it's about real estate and it's about political power. As part of the continuously shifting point of view in this film, we see part of the fighting through the eyes of Neda, who has saved Luke. Of course, she is lecturing him from her angle, advocating her take on the fighting and the killing, which doesn't automatically make her right. And Luke's answer is: "Oh, I'm sure you'll be really nice to the Turks if you win." We see the leader of the Macedonian rebels, the Teacher, as a ruthless murderer who kills a scared young soldier by slashing his throat. The Macedonian revolutionaries also shoot wounded soldiers. On the other hand, the Turkish army kills civilians. And they did, historically. It's really hard (not to mention unethical) to make films according to p.c. [politically correct] scenarios of how the world should be if you happen to be portraying events that weren't p.c. Most of history was not p.c. At the turn of the 20th century the Ottoman army would go into villages and kill civilians, even pregnant women, would burn young children alive and chop peoples' arms and heads off. That is a documented fact (and, unfortunately, this was not the only army that did this). So I don't see why it constitutes a prejudice on anyone's part if this historical truth is being mentioned or portrayed. Sounds like a chip on someone's shoulder. (Yet, focusing only on painting this or any kind of historical truth alone should not be the sole goal of a good work of art; good art deals with aesthetic interpretation of people's feelings and philosophical concepts.)

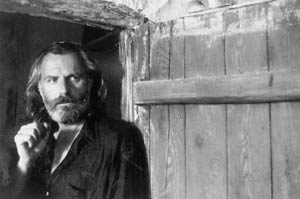

I am prepared to debate the actions of the Ottoman army in Macedonia at the turn of the 20th century, as well as the actions of various revolutionary and criminal and nationalistic and self-serving gangs. I strongly object to interpreting the portrayal of the Ottoman army in Macedonia as a metaphor for anything but the Ottoman army in Macedonia, as some respected German newspapers did (who claimed that the Ottoman army was a metaphor for the Albanians in Macedonia). I think that's in the eye of the beholder, and taking him to the eye doctor would provide for a fascinating look into one's psyche. May I ask about one thing that's not really political? The Turkish major is the most amazing character… Precisely! If you were a racist, why would one of your most complex characters in the film, and the most urbane and the most educated, be of the people you are trying to slander?

Exactly! Was he modeled on a particular person? No, he wasn't, but he was based on research. I started with the concept that the Ottoman officers were some of the best educated people in the Empire. It had been a powerful - in many respects admirable - multi-ethnic empire, at this point nearing its sunset. The Ottoman officers were well-educated and spoke foreign languages. From the research that I did (our core bibliography consisted of 160 books and articles written at the time and about the Wild West and about Macedonia under Ottoman rule), some were trained in Germany and had strong ties with the German military. This particular character, the Major, speaks German, he speaks French, we don't know whether he speaks English or not, but he does tell Luke that he doesn't speak his "barbaric language." He makes a point of that. Because to him, this character is an illiterate punk, a bounty-hunter from this remote corner of the world (America), who's come here to try to make a living… by meddling in the local affairs… and all for money. The Major has a very strong sense of duty. To him, none of this is personal. He does say: "Look, these people are fighting against my emperor. And I have to protect him. It's my duty to find them and bring them to justice." He is one of the few characters in that place who has a very strong sense of order. But it's interesting in this context to actually get a little more analytical and look into what it is that makes a film reviewer be so obviously biased. Is it something in the film that provokes people to project their own prejudices and their own problems upon this film? Or is it something off-screen? Is it my attitude to the stale and corrosive film industry? Or does it have to do with the current politics of Macedonia at the time? Does it have something to do with the op-ed pieces that I published just a couple of weeks before the film came out? What did you say in those pieces? It was actually one piece, which was written for The New York Times, but they didn't publish it. Yet somehow, it made its way to The Guardian. When they published it, they changed the title and chopped off the end. And took out some other things. There is a journalist in Slovenia who published a parallel of the original article and the article that came out in The Guardian. Then I submitted it to a German newspaper - I think it was the Sueddeutsche Zeitung. Pravda in Russia picked it up, as did the Standaard in Belgium. I don't know whether any of these newspapers published it in its original form or whether they changed anything, like The Guardian. The gist of the argument was that NATO had a major (but not sole) responsibility for the spill-over of the Kosovo war into Macedonia, and that they had to act upon it. And that they had to protect the order and sovereignty of Macedonia. As they didn't. And at the time, I was comparing it to Cambodia or Laos or to Afghanistan, as examples of spill-over and blow-back (this was pre-9/11). A lot of the people who instigated the fighting in Macedonia in 2001, who killed soldiers, policemen and even civilians were armed and trained by NATO for the war in Kosovo. That's what this article was about. And actually the Standaard in Belgium published the article and then published the response by an Albanian. It was signed "an Albanian student." A person I don't know. First of all, it was strange that they would publish such a response because I wasn't taking nationalistic sides. I was taking the side of rule of law versus armed intrusion. Also, in terms of media manipulation, I was raising the following issue: accepting that somebody can just pick up arms and kill police because they are allegedly fighting for language rights, is something the West doesn't accept at home, but can accept in the Balkans, because their projection of the Balkans is as an unruly bunch. There was a high-ranking NATO officer saying that every house in Macedonia has a gun. I want him to come and find the gun in my house. See, that's racist. (How would that officer feel if someone said that every house in Germany is anti-Semitic.) So when there's fighting, in their minds it's not because somebody's killing policemen. It's because: "Oh, two ethnic groups are fighting." Wild tribes. But, that was not the case in Macedonia (and I hope it stays that way). As is becoming clear today because some of the people who were supposedly fighting for human rights and language rights two years ago are now on the list of human-traffickers and drug-smugglers, and some are government ministers and parliamentarians. Let's put it this way: if somebody picked up arms to kill policemen in Miami because the killers claimed that they wanted Spanish to be spoken in the Florida senate, I believe those people would be shot or put in jail. NATO wouldn't come to mediate and take the situation to a point where those very same murderers sit in the parliament two years later, as is the case in Macedonia. Anyway, what happened in the Belgian Standaard was that they took the article as though it advocated one ethnic side when it was actually advocating the rule of law. So they published a response by someone signed "an Albanian student," whom I didn't know. And that same person is the vice-president of the Macedonian parliament now, today, as a representative of the political party which came about with the transformation of the Albanian militants. I'd be curious if he were a student at the time, since he seems to be in his late 40s. So back to the really interesting question: is it something in the film that provokes some reviewers, particularly those with a chip on their shoulder? Or is it things outside the film? Was it the articles? Was it the war in Macedonia? Was it my earrings? (Laughter.) Was it the fact that this film opened the Venice Film Festival? Was it the fact that I pissed off so many people in the industry in the seven years between Before the Rain and Dust? (I refused to play by the industry rules, to accept unethical standards and the dictatorship of the oxymorons - creative executives - over the artist. The film industry both in Hollywood and in Europe stifles creativity and is an extension of repressive mechanisms. Censorship is so ingrained and often self-inflicted that no one even raises the issue. I felt it was my duty to fight it, and I made a lot of enemies along the way. The industry paid back by strangling the film in the crib, so the regular viewer never got a chance to see the film.) Was it my unpaid bills to Screen International? (Laughter.) I'd be really curious because if it is something in the film itself, as a shrink friend of mine claims, that would be really something. That means there's something in the film - whether it is the characters themselves (none good, none bad, most created from clichés/archetypes that have been inverted) or the actual relationships between the characters (stark), or the way I have treated violence and compassion and sex and self-sacrifice that has triggered such a violent outburst from many film reviewers and not nearly so from the very few regular movie-goers who got to see the film. Or, is it the fact that Dust subverts our expectation that a film has to have neat linear structure and - more importantly - simplified and uniform emotional template (a horror is a horror, a comedy a comedy)…? You could argue that it's not pleasant to be at the receiving end of bourgeois anger, or you could compare the level of animosity to the way some other artists have been received for their non-conformist works: Rules of the Game, Cubism, The Wild Bunch, Bunuel, Joyce, Nabokov… I am interested in Cubist storytelling - when the artist fractures the story and puts it back together in a more complex (and, thus, more interesting) way. More importantly, when the artist keeps shifting the emotional tone of the film, bringing a narrative film closer to the experiences of modern art. Either way, that's not something for me to judge. At least not at this date. Maybe ten years from now, when I have a perspective to the film, I'd be able to judge a little more clearly. Maybe I'll see it then and I'll decide that I'd made a bad film -- or maybe not - yet the value of the film doesn't justifies the prejudiced and violent assassination of Dust by the industry gate-keepers and political pundits. Concerning your portrayal of storytelling in Dust, I don't have a specific question. I was just hoping you would tell about your preoccupation with showing the very process of storytelling. I think it has its roots in two things. One is my interest in structuralist and conceptualist art. On the surface, the form of Dust is not that of a structuralist or conceptualist piece. But, in its own way, it picks up on what these movements were trying to tell us, and builds it into the popular idiom of narrative film. You have to take into consideration the inherent elements (and expectations) typical for film as a story-driven and popular discipline and then incorporate them into the film. The second thing is that, just like any artist, I'm making autobiographical work. Since I am a storyteller by interest and by profession, I became preoccupied with exploring and exposing the process of storytelling, but more importantly, with exploring the thirst to tell and to hear stories. I am not talking only about storytelling in film. I'm talking about writing, oral tradition, teaching, journalism, fairy-tales, myths, legends, telling jokes, bed-time stories, religion, writing history… it's actually such a huge part of society. And it's probably more essential than we are aware of or than we would acknowledge. It's one of the main modes for teaching and learning from each other how to behave, what life and society are about. Storytelling is the nervous system of society. As I was making films, I became more and more interested in the essence of what it is that a viewer wants from storytelling. I realized we look at stories, but don't see the storytelling. Even when it's to the detriment of the listener. So, I went with the assumption that if I strip the process for the viewer, and then incorporate it in the story, that he or she would come for the journey into the nature of storytelling. The viewer would be involved in unmasking the process (while still keeping it somewhat part of the illusion) and maybe get a different kind of pleasure from this kind of a ride -- as opposed to just being a participant in a ride which is all about the illusion, the mask, the manipulated unified feeling. Perhaps one would enjoy this complex (and fractured) ride better and learn more about this aspect of our social lives. Mainstream narrative cinema is all about expectations, and really low expectations, to that. We have become used to expecting very little from the films we see, not only in terms of stories, but more importantly and less obviously in terms of the mood, the feeling we get from a film. I think we know what kind of a mood and what kind of a feeling we're going to get from a film before we go see the film. It's from the poster, from the title, the stars, and it's become essential in our decision-making and judging processes. I believe it's really selling ourselves way too short. I like films that surprise me. I like films that surprise me especially after they've started. I like a film that goes one place and then takes you for a loop, then takes you somewhere else, and keeps taking you to other places both emotionally and story-wise… keeps changing the mood, shifts in the process, becomes fearless… All of this needs to be unified by an artistic vision, making it a spirited collage, not a pastiche. A Robert Rauschenberg. In the end, I'm surprised to see that it's the reviewer rather than the regular movie-goer who expects and even demands to see a film limited, predictable, subservient to expectations, a film that neatly and vulgarly folds within the framework of a genre and a subgenre. It's especially sad when the genre in question is what used to be known as "art film." New York, 11 October 2003

|