|

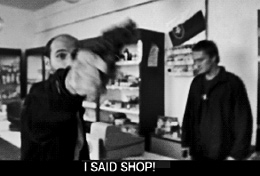

The t-shirt is a highly American and democratic piece of clothing. It is democratic because it is affordable, somewhat generic, accepted and therefore levelling, but also because it can be used to proclaim a point of view. These two uses of the t-shirt clash in the short film T-Shirt from 2006, written and directed by Hossein Martin Fazeli. Both protagonists in this eleven-minute film wear a t-shirt, one which is generic and one that bears the imprint "'God is … dead', Nietzsche", and (on the back) "'No, Nietzsche is dead', God". The gradual and partial disclosure of this imprint to the other protagonist constitutes the main structure of narration. The larger context for this, and the reason that it holds any worthwhile significance, is the exacerbated fissures between places, (religious) values and American positions in general but more specifically in the long aftermath of 9/11; that the film is set in the present while held in black and white certainly seems to underline its more general references. And so does the use of the T-shirt and its uses as a main prop, which points to an ever-present tension between repressive conformity and difference within the public culture of the US. At the opening of the film, we follow a lone driver in a four-wheel drive cruising through rolling hills accompanied by gospel-leaning music whose lyrics state that travelling "through this world we leave a trail behind of suffering and sorrow"; and as we cut from a shot of the driver in profile to a cross dangling from the rear-view mirror the female singer intones: "I think about the people that I've wronged, hurt and scarred" after which the next shot presents us with a photo of a soldier glued to the glove compartment underneath a sticker that reads "God Bless America".  A mixture of visual and aural clues thus coalesce personal, national and religious trajectories, emotional and physical violence, and - not least - temporal and spatial movements through which a reminiscing viewer, (driver/nation?) is hurled into the future; with the images of the dangling cross against the blurred movements of the oncoming cars and landscape the car leaves the viewer behind while the singing develops into fully-fledged gospel call and response wondering "whether peace will ever found this world". We somehow know where he, they (us?) has/have been - but we do not know what is coming. Almost everything in the iconography and music suggest that this is, so to speak, an internal affair, i.e. a delving into some of the domestic consequences, perhaps even doubts, related to America's military engagements. And when the soundtrack pulls us onto an attendant in a roadside shop watching baseball on TV while practising with his own baseball bat this seems not only confirmed but underlined by the American flag on the wall behind the counter as well as the Texan license plates of the car when it pulls up at the store. Yet there have been and are also signs that contradict this impression, signs that may suggest tension and incompatibility in addition to tensions already introduced. First of all there is the road sign saying "Bratislava 22", which we see as the car is propelled away from us into the landscape. Although there surely is a small town of that name somewhere in the US, the style of the sign seems different from American road signs.  And then there is the lack of outdoor advertising as we approach the roadside shop as well as the very subdued storefront. This is not the brazen public imagery of America! And this is somehow underlined by the indeed very sparsely furnished shop, whose lack of merchandise and commercial imagery is ambiguously underwritten by the presence on the counter of a book called Pustatina , the Slovakian translation of T.S. Eliot The Waste Land . Through the conversation between the shopkeeper and the driver it is soon revealed that we are in fact in Slovakia - which explains the Slovakian flag next to the American on the wall behind the counter. That there in fact is a place not far from Bratislava called Pustatina Stara Guta, and linking the scarcity of this region with an American poetic universe, the Waste Land, swiftly transforms the narrative's intertwining movements presented at the beginning of the film to (also) concern America as an ideological and physical force outside its own territories, which - as much as anything else - makes this a story about the role of religion within intercultural relations. As such, this seems the beginning of a beautiful friendship. It turns out that the driver is an American of Slovakian heritage living in Houston, who is currently back visiting Slovakia. It also turns out that the two men share an interest in baseball and the driver encourages the shopkeeper to look him up if he ever gets to Houston, and the driver also proclaims that he will "be shopping here more often if only for the flag and the T-shirt" - of which only the "God is …" visible.  Encouraged by this the shopkeeper pulls aside his jacket to reveal the whole imprint. This is where things start to go wrong, and a re-emergence of aspects of the social, emotional and physical violence suggested by the lyrics, the photo of the soldier, and the baseball bat beneath the counter seems imminent. The ensuing tension had, however, been anticipated by the divergent interpretations of the Slovakian region referred to by the visitor as his "mother-land", a comment swiftly and fatalistically countered by the shopkeeper sneering "The Wasteland!" "No", says the visitor, "it's a beautiful country. Really beautiful". What is opposed here are on one level somewhat polarised materialities and linked perspectives, i.e. the American four-wheel drive from which the region simply is beautiful and the actualities of making a living in the region. This split between a somewhat globalized tourist gaze and a view grounded in necessity is somehow paralleled by the double-ness of the Pustatina reference, which links materiality to notions of faith, and its questioning, an opposition mirrored in the Nietzsche quote and the "God Bless America" sticker. Confronting each other are thus material conditions as well as ensuing and contradictory perspectives on Christianity, faith, morality and direction. Initially, however, the visitor merely objects to the T-shirt being exposed together with the American flag. Those signals are, he asserts, incompatible since "most Americans believe in God and the flag at the same time". "[B]ut, this is not America", answers the shopkeeper. The visitor does, however, strongly advise him to remove the flag "so people like me wouldn't feel insulted when they come to your store". Instead, replies the storekeeper, I should "post a sign on the door that says: 'Intolerant people do not enter!'" This is my territory", he says, and "I can do whatever I want in it". Caught in a difficult situation and apparently lost for arguments, the Slovakian-American resorts to solve the crisis through money: he throws a large bill on the counter and asks the "kid" to get a new shirt. As pointed out above, a lack of faith seems here somehow correlated with material scarcity; but the attendant does not "need a new shirt" and under his breath he calls the visitor a "fucking asshole" as he is about to leave the shop. In the heated exchange that follows the shopkeeper likens the visitor to the Taliban in their essentialistic approach to symbols and intolerance of others' point of view. It turns out, however, that the photo in the car is of the driver's brother just killed in Afghanistan. The enraged visitor finally pulls his gun and forces the shopkeeper to take down the flag and hand it over. As this is happening another customer enters the shop, picks up a few things, and turns toward the counter where the shopkeeper still has the gun pointed at him. Seeing this, the customer drops his things and turns towards the door. "This is not a robbery", says the visitor, "We're just having a discussion", and he thereafter tells the customer to relax and finish his shopping but the customer remains hesitant. The driver turns around and points his gun at him and exclaims "I SAID SHOP"! In the brief interval before he turns back towards the counter, the attendant has managed to pick up the baseball bat and hits the driver, who collapses on the floor. The attendant phones an ambulance, takes off his jacket, lights a cigarette and walks out the door and thus exposes the back of his T-shirt that says "No, Nietzsche is dead', God", while gospel singing returns with the claim that only the Lord can give meaning to your life. The opening and closing lyrics match the T-shirt's front and back - the impossibility of not leaving behind a trail of sorrow and suffering but also of a world where we might need something to believe in. This is a manifestation of the need for faith at the same time as its impossibility, and it is certainly also a comment on the role of faith in intercultural relations. The American attempt to control cultural events, to enforce a religious and democratic tolerance through soft and hard power, i.e. money and guns, is certainly exposed as a failure in the condensed closure of the film; and so are the implied links between materiality, faith and development. This comes out very clearly in the scene where the driver points his gun at the customer and shouts "I SAID SHOP!", and also in the irony of calling the exchange at gunpoint a discussion.  The central point, however, concerns the T-shirt. Its failure to takes sides, its relativity or fatalism, is, however, not the central issue - the point is rather who decides and where. The imprint in the back may have appeased the driver somewhat; but the attendant chooses not to show it - arguably because he welcomes the confrontation with the Slovakian-American as an opportunity to assert his independence. If the store looks somewhat empty, the Slovak's certainly has his arguments stocked up and ready. He might be living in a waste land, but at least it is his; if the price of material wealth is an increased conformity, he is not interested. What is ultimately at issue here are different and opposing means through which territories (or communities) are construed and/or sought upheld, i.e. citizenship, heritage, (religious) symbols, money, guns or other types of violence. No clear answers are presented here; what is certain, however, is that these struggles also are played out in everyday processes, which may include both burkhas and T-shirts. Although the acting may seem a bit stiff at times, the film's ingenious use of narrative structure, iconography and mise-en-scène manages, through modest means, to turn this into a timely exposure of some of the ironies and ambiguities of the American notion of a world mission as it has been played out in the post-9/11 world. | ||

|

| ||

| ||