|

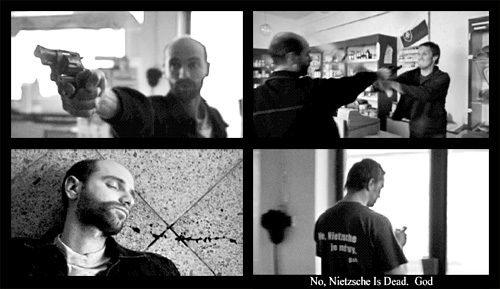

As film-making becomes an increasingly available option across the educational system in general (and not just in film schools) so the number of shorts that get made every year increases exponentially; no single person can possibly keep up with the output, and it must be true that many fine apprentice films disappear under the radar - sent to the wrong festival or to no festival at all; condemned to be seen merely by the film-maker himself or a restricted circle of his acquaintance. So festivals are important; they help to give some shape to the map; they sort out - or help to sort out - the wheat from the chaff. Hossein Martin Fazeli's T-Shirt has won a number of prizes and one can see why. It has the extra 'something' that most shorts don't - a shape, an authority, an objectivity. Yet what actually are we responding to when we state our intuition that a film has 'authority' and 'objectivity'? What quality or concatenation of qualities combine to allow us to judge such a work to be above the common run? We may note first of all that Fazeli's drama limits itself to a minimum of locations: essentially, a few establishing shots inside Mark's car as he's driving through the Slovakian countryside; then an exterior of the shop he stops at, followed by our moving into the shop itself where the meeting takes place and the story unfolds.  Along with this unity of place goes a unity of time . The film describes a single incident as it plays itself out from beginning to end, in all its ramifications. In making these preliminary script choices, the film-maker seems to pay homage to what a short film can, and what it can not, do. It can't, I think, have a multiplicity of locations and time-frames if the effect aimed at is one of intensity and coherence. The 'necessary minimalism' observed here by Fazeli in turn allows him space for the things that really are important - in this case, for the acting of either principal to smolder and catch fire. To say there is 'real acting' in Tricko is another way of noticing how relatively rare this is in the short film genre as a whole - not, primarily, because of the inexperience of the actors involved (who in the nature of the enterprise are generally not professionals) but because, most often, there simply isn't space for it - the film-maker's attention lying elsewhere (elaborating his plot, or honing his camera angles). So it is intense, then, and 'real', this psychological confrontation between Mark, our young 'tourist-revisiting-his-motherland', and Tomas, the shopkeeper of roughly his age into whose territory he happens to stray one fateful day. At first all is as calm and friendly as one would hope for. The two men exchange the standard civilities that pass between customer and service-provider. Mark, of Slovakian parentage, has been brought up in the United States; while Tomas, the shopkeeper, his contemporary, is indigenous. The young men belong to the same generation, and they may be expected to share some of the cultural attitudes that go with this. For example: 'internationalism', of sorts - the internationalism of travel, of sport, of pleasure taken in jokingly-captioned T-shirts - is a good in itself. Is it not? Maybe not, it turns out. The dialogue recording the gradual change of temperature between the men as an 'incident' brews up out of their initial pleasant banter, is masterfully extended. In substance, it is the film itself, and it allows the viewer to remark that if, as we have agreed, the film is extremely well-acted, it is because (another 'quite difficult' thing to pull off in shorts) it is correspondingly extremely well written . There is body and depth and subtext in the icy exchanges about patriotism and God that suddenly flash up between the two. The mutual ripostes are eloquent without being stagy. The least you can say about this central confrontation in the film is that the person who imagined it knows - in an impressive, serious and adult way - how to write dialogue . Yet I am tempted to think it is rather more than this: for what Fazeli has pulled off here is the one thing that has to be pulled off for a short film to make sense: a peripeteia in miniature - I mean by this a turn, or transformation, whereby what we thought we were watching turns out to be another thing altogether. It takes us by surprise - this sudden change of temperature in the movie when violence leaps up out of nowhere. At one moment, everyday banter; the next moment, a glimpse of the abyss. The 'turn' I am talking about here is to be distinguished from another species of turn that belongs characteristically to the short film genre: I mean the punch-line or 'twist'. Certainly T-Shirt also possesses such a feline sting-in-its-tail, nicely sly and sardonic. Just to remind the reader: the quarrel has flared up between the men because of the caption on the front of Tomas's T-shirt, which reads, in Czech, 'God is Dead - Nietzsche'. According to the now-revealed right wing ideologue Mark, it is an 'insult' to sport such a message while standing beneath an American flag. Baseball-mad Tomas disagrees, and says so, with some of the eloquence I have attempted to intimate. Events take their course and when it is all over (Mark lying comatose on the floor) we see from another angle the other side of the offending T-shirt: 'No: Nietzsche is dead - God'. An excellent joke in its way (Tomas's even-handedness in giving God the last word 'proves' his liberalism, of course) - and all the better for being understated. (No importunate close-up: you catch the allusion or you don't.)  Yet thinking about this specific case allows one to reflect on punch-lines in general and whether their appearance, in short films, is 'desirable'. The best shorts, I think, have a habit of ending where they will: they don't need punch-lines because they are confident that what has transpired can stand by itself without the aid of an artificial closing device. The problem with punch-lines (admittedly, not everyone thinks there is a problem) lies in the unavoidable glibness which enters the aesthetic equation when the integrity of the story is thrust aside in the interest of demonstrating, or upholding, the film-maker's self-evident cleverness. Cleverness, surely, is never the ultimate criterion where drama is concerned. (In comedy, on the contrary, it may be everything.) These last observations suggest, I suppose, that I have certain qualifications about T-Shirt. Does it package its message too neatly? Does it wear its liberal heart too blatantly "on its sleeve"? I suggested above that one of the great qualities of art is objectivity. The audience doesn't want to know what a film director's social views are. In Carl Th. Dreyer's Vredens dag (1943) the 17th century Lutheran church is attacked for its benighted confusion about witches - a confusion that is not so different from wickedness. But the church itself, qua institution, has power and dignity and eloquence, and Dreyer does not make the mistake of painting it in the uninteresting colours of caricature. ( That mistake is reserved for a later luminary, Lars von Trier. In Breaking the Waves the portrait of the reactionary Presbyterian Church in Northern Scotland is boringly facile and undifferentiated.) T-Shirt, of course, is clearly an 'anti-fundamentalist' document. It speaks out against religious intolerance, and that is something that we, as citizens, may all agree about. Yet maybe Mark's right-wing fanaticism is 'given' too explicitly? Seeing the film for a second or third time is to note how naked its signifiers are from the outset: the crucifix dangling from the car's windscreen; the photograph of Mark's brother in military uniform attached to the dashboard (along with the printed legend 'God bless America'); the Texan number plates (Bush's territory); the fierce, Travis Bickle-ish stare of Mark in profile; the gospel music on the soundtrack. Certain responses are designed to be 'triggered' here. The song, not the t-shirt caption is in fact the film's punch-line. We hear its words picked up again over the final credits, by which time they have taken on a quite direct explicitness. 'Will Peace ever get found in this world when Love gets lost on the way?' wails the singer (Zuzanna Stirská). That, of course, is the film's 'message'. Yet, after all, we reflect, it is a question not a statement ; and the song itself has a raw power - a seriousness - which may be allowed to absolve Fazeli from indulging, at the conclusion of his elegant short movie, in a too facile post-modernist irony. | ||

|

| ||

| ||