The core of any story which is satisfying to its public, is a chain of cause-and-effect relationships. In Aristotle's words, "whenever such-and-such a personage says or does such-and-such a thing, it shall be the probable or necessary outcome of his character, and whenever this incident follows on that, it shall be either the necessary or the probable consequence of it."[1] This principle has remained a cornerstone of narrative theory and of works on the crafting of fiction, which define a story as a sequence of causally related events.[2]

The Price is Right is, like any other successful story, constructed as a causal chain, though to a greater degree than is usually the case, the causality in play is left implicit rather than spelled out by having both cause and effect shown on screen.

For example, when Zev's buzzer stops working in the midst of his winning streak on the quiz program (Scene 12), we are left to work out for ourselves that some producer in a control room has apparently instructed that the buzzer be disconnected in order to make the contest less lopsided and more interesting for the viewers. Another filmmaker might have chosen to include a shot of the producer giving the order; Daphna Levin, the writer/director of The Price is Right, admirably left it up to us to work out the cause of the buzzer failure-in much the same way that the punch line of a good joke requires that the listener figure out the logical connections involved.

|

|

|

|

Considering the road she has traveled from those early scenes until the final moment of the film when she naughtily slips out of frame, we may wonder what catalyzed the changes that must have taken place in her.

One way to connect story elements is to suggest that Zarchit overcomes her shyness as a result of having for the first time the upper hand in her relationship with Zev. Until then, he was-despite his own shy and retiring nature-always the infallible one, the expert, and she was generally at a loss. Now, he has suffered public defeat, and for once she can be supportive and generous toward him.

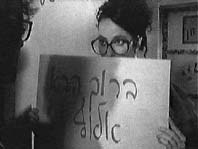

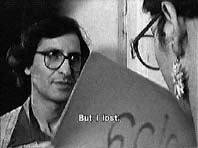

This can be seen most clearly in Scene 14, when she holds up the "Welcome Champ!" sign, to which Zev dejectedly replies, "But I lost." The second sign she then holds up, upside down at first (as a reminder of the awkwardness she is in the process of shedding), says: "You'll always be a champ to me"! Never before had she been in a position to lift him up.

|

|

This was, I believe, a plot necessity, designed to give Zarchit the upper hand at the end, and in that respect, this too involves a form of causality.[3] There is no mention in Scene 14, as there had been in Scene 8, that Zev was covering for Zarchit, because that would have made her indebted to him and what the plot called for at the end was for her to be in a giving position-which in turn helps explain her new found self-confidence and boldness.

We can also make connections between story elements by taking another and very different pathway as well. The fact that Zev sacrificed an otherwise certain victory on television in order to keep his promise to Zarchit, could be seen as giving her a new sense of her importance to him, which in itself could be a factor in overcoming her shyness.

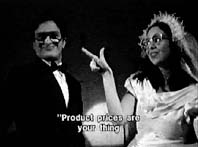

In any event, her transformation is given visual form through the attractive hairdo, make-up, earrings and evening dress in Scene 14, and then is taken a step further by the wedding gown and crown-shaped headdress she wears in the final scene. An additional visual factor, better enabling us to accept her almost total transformation, is the set used in the final scene-the same one that had earlier been used in Zev's dream in Scene 9, in which Zarchit appears as a woman who is perfectly at ease with her sexuality.

Zev's dream in Scene 9.

Zev's dream in Scene 9. |  The final scene.

The final scene. |

2 See for example Gerald Prince, The Grammar of Stories (The Hague & Paris: Mouton, 1973), pp. 26, 28; and John Gardner, The Art of Fiction. Notes on Craft for Young Writers (New York: Vintage Books, 1991; orig. pub. 1984), pp. 53-56.

3 In Narrative Fiction: Contemporary Poetics (London & New York: Routledge, 1993; orig. pub. 1983), Shlomith Rimmon-Kenan distinguishes between two forms of causality, explaining a fictional event a) "according to the logic of verisimilitude" [by which she means: in terms of character motivation]; or b) "according to the structural needs of the plot" (pp. 17-18). She rightly points out that it is important to distinguish between these two forms of causality. I would only add that the second one-such as the screenwriter's need to get rid of a given character so that the plot can advance in a desired direction-is far too rarely invoked with respect to understanding cinematic fiction.